What Does it Mean to Be Human? Punk, ‘Blade Runner’, and Philip K. Dick’s Electric Dream

If there’s anything I hate, it’s subcultural neologisms. Not subcultures, mind you, which are exciting and strange and dynamic, but rather the label-making that cements a taxonomy in a larger social lexicon. It’s foul magic, naming something to rob it of its potency. You inevitably trade whatever inspiration and energy that went into first creating some weird fellowship for a quick and easy (and marketable) name, immediately diluting your movement into weak tea. This is aggravated by your average cultural nomenclaturalist being more of a splitter than a lumper, dividing and subdividing like a mad Linnaeus in search of ever more “natural” categories of pop culture.

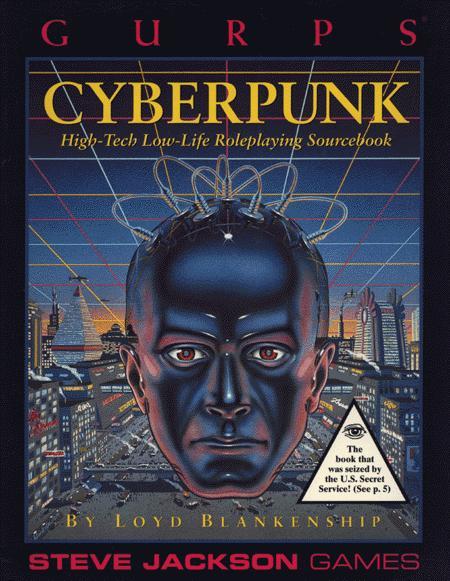

The dumbest neologizing is a “whatever-punk” formatting for your goofy little club, and the dumbest prefix to attach to “-punk” is “cyberpunk” (narrowly beating out “steampunk”, if only because “cyber” faux punkery is the horrible patient zero of the whole phenomenon). Sadly, the origins of that grim little scene go back to Blade Runner (1982) when a bunch of geeks ignored any actual anti-authoritarian punk sensibilities and instead got enamored with the transhumanist wankery and spruced-up Gothicism of Ridley Scott’s neo-noir aesthetics.

Fuckin’ nerds.

In fact, William Gibson, patron saint of cyberpunk bullshit, has said he walked out of Blade Runner after the first fifteen minutes. He was shocked by how close the visuals of the film adhered to his own then-embryonic novel Neuromancer and didn’t want to absorb too much of it before finishing his book.

That sums up everything wrong with what “cyberpunk” turned into; their love of “surfaces” never digs deeper than the boring romanticism of fascist oppressors versus the plucky underdog. They have the same sensibilities of Civil War reenactors or LARPers in their unabashed love of a specific style. In their excitement over playing dress-up, they write (or film) neo-futurist love-letters to smoke and grime and elephantine industrialism without ever interrogating the social and cultural landscape they are evoking, falling back on the simple hagiographies (and adolescent fantasies) of The Rugged Individualist of bad noir.

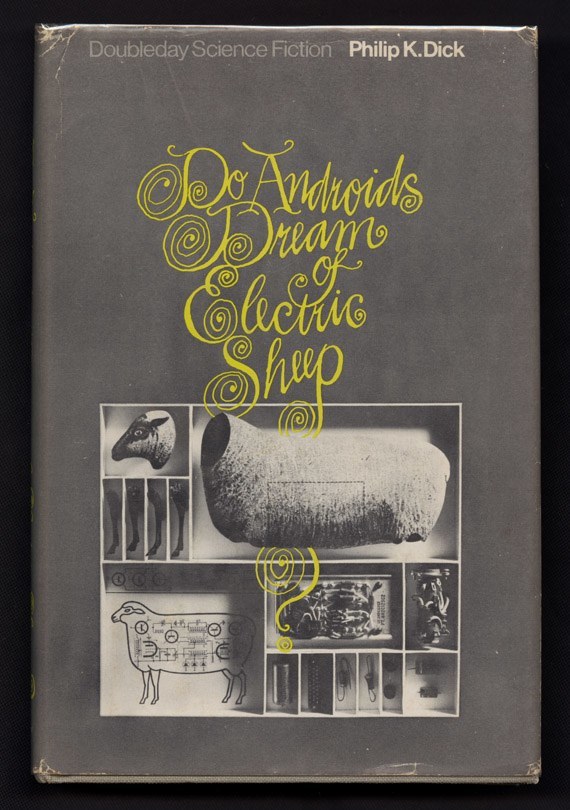

The ultimate failings of cyberpunk’s evolution are a real shame, for two reasons: 1) the literary progenitors of cyberpunk, including Samuel Delany, Stanislaw Lem, Harlan Ellison, and the Notorious PKD, all articulated a legitimate punk philosophy in their work, exploring Foucauldian biopower, technology, and individual strategies of rebellion before those ideas were the keywords for academic papers and; 2) Blade Runner is a fuckin’ great movie, and despite not being a strict adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep (1968), it is spiritually faithful to PKD’s themes and interests.

Electric Sheep is certainly Dick’s most famous work, attached as it is to one of the best movies ever made. It’s also a touchstone of how the media-consumin’ public views Dick’s work as interesting but ultimately unfilmable, requiring substantial reworking in order to make it to the big screen. That’s too bad, because while Ridley Scott hadn’t read Dick, his screenwriters (Hampton Fancher and, after Fancher left, David Peoples) certainly had, and were at least aware enough of Dick’s themes to build on them for the screenplay.

God, how many terrible garage bands have called themselves “Electric Sheep”? We may never know…

Dick’s overarching theme in Electric Sheep is, as always, “humanness”, although not necessarily in the way people commonly assume. A lot of readers interpret Dick’s writing as him exploring a platonic binary, where there is a Real And True Definition of “human” out there somewhere. In fact, Dick is much more interested figuring out how people CONSTRUCT “humanness”.

In Electric Sheep, World War Terminus has resulted in a mass flight from earth, with most people living on the off-world colonies like Mars. Much of earth suffers under clouds of radioactive dust. The resultant environmental disaster has produced an unprecedented ecological crisis, with Permo-Triassic extinction levels measured in months rather than 10,000 or 100,000 years. The people that have stayed on Earth are subject to constant evaluations of their reproductive fitness, the prime virtue sought for inclusion in the new human society being founded in the off-world colonies.

Business plan: Like Uber, but for inner-city zeppelin advertising.

Some people, however, feel a deep connection to the ruined Earth, linking their “humanness” to living on the planet of their birth. Those that remain make their living as best they can, the men protecting their gametes behind stylish lead codpieces in case they ever do want to leave Earth. Additionally, a thriving and very expensive pet trade has developed, commodifying conspicuous displays of empathy as a means of reasserting one’s fundamental “humanness” to their neighbors. Being able to afford a pet, to keep it alive and healthy and happy, is a way of communicating to everyone else that you are a human, that despite this terrible, depopulated, toxic world, you still possess the capacity for empathy and care.

Viable reproductive faculties and the capacity for empathy (which is, of course, a reproductive and child-rearing strategy) are what the characters in Electric Sheep have decided makes them human. And it is the absence of the same that leads them to identify the “andys”, organic android slaves, as less than human. The paranoia sets in when you realize that, at least from a superficial standpoint, these non-humans can pass as human; this is, of course, intolerable, and so there are secret countermeasures in place to “retire” any andys that make their way to Earth. Richard Deckard is one of these countermeasures, a bounty hunter contracted secretly to kill escaped androids.

Much like the murderbots in “Second Variety”, the technological sophistication of newer androids has resulted in a kind of arms race between android manufacturers and those charged with detecting them. Tests of increasing sophistication must always be developed, but as a byproduct, the line separating human from androids becomes more and more reductionist. Under the Voight-Kampff test, “humanness” becomes a search for autonomic physiological responses that signal a subject’s capacity for empathy.

Of course, Deckard’s faith in the meaningfulness of involuntary eye twitching as an unambiguous indicator of humanness is tested when he meets an honest-to-God murderous sociopath working as a bounty hunter. His callousness and the apparent joy he takes in killing makes Deckard think he’s an android, but dude passes the ol’ Voight-Kampff with flying colors. Similarly, the Nexus-6 androids he’s hunting turn out to be working pretty efficiently together, something non-empathic androids are not supposed to be able to do. What, then, does Deckard’s (and the rest of humanity’s) definition of “humanness” mean?

Behind all the cool noir flourishes and the smoky synth of Vangelis’s (completely rad) score, Blade Runner does a good job of interrogating that same theme. Replacing a depopulated earth with an oppressively overcrowded one dominated by literally stratified megacities carries Dick’s message of creeping capitalism through, although it’s a much more conventional consumerism than the pet-based empathy markets of the book. The heavy-lifting, thematically, falls to two characters, both substantially different from their book origins.

Vangelis…in SPACE. Gonna get this painted on the side of my van.

Sean Young rocks both the shoulder pads and the expanded characterization of Rachel the replicant who, in the movie, is unaware of her status as a manufactured being. While the Rachel in the book is a Machiavellian android provocateur, Rachel in the movie is the one replicant whose victimization is shown to the audience. Her realization that nothing is hers, not even her identity or memories, is an existential death presaging her own programmed death, either at the hands of a state-sanctioned blade runner or as a result of intrinsic biological self-destruction. Both of these outcomes are the result of the actions of her literal owner, a standard issue Reagan-era corporate monolith.

Sean Young, in the happy days before Ace Ventura: Pet Detective.

Roy Batty (Baty in the book), on the other hand, is a replicant whose entire life has been circumscribed by his status as less-than-human, and is now facing the reality of his own death as a result. In the book, Baty is an unhinged messianic prophet, someone who aped human religiosity in hopes of experiencing transcendence. When that proves impossible, he and his compatriots go on a killing spree and escape to Earth. The movie version of Batty, played heroically by Rutger Hauer, hopes for a technological fix that will give him more life and, when denied, goes ballistic on Harrison Ford (we’ve all been there).

All while wearing bike shorts, too.

Batty’s last scenes suggest either he’s taken Tyrell’s advice to heart (live life to the hilt) or he’s demonstrating a capacity for empathy. Hauer’s famous “time to die” speech, what with its rad sci-fi names and poetic cadence, seems to indicate that, at the end of it all, he’s only got his memories – does sharing them with Deckard give him some peace, illustrating to the audience that interconnectedness with other humans is the only thing that saves us? Maybe it demonstrates the fragility of life, a lesson Deckard puts to good use by escaping with Rachel at the end of the movie?

Regardless, Blade Runner shows how the flexibility of Dick’s vision (along with a sizable budget and a steady hand at the tiller) makes for a good movie, because Dick’s vision is never about the technology. Contrary to what a lot of futurists say, Dick wasn’t presentient in his writing; rather, he was simply universal, understanding that at its core the human experience is one of learning to define ourselves, sometimes concretely, sometimes fluidly, but always in a wider social context. It’s disappointing that the cyberpunk movement didn’t catch on to that, because it’s a very punk sensibility.

Admittedly, Robert Redford is pretty punk.

Dick’s characters suffer because they believe in platonic ideals and an unchanging universe. Character growth in a Philip K. Dick story occurs when they realize that the ground under their feet is not as solid as they thought it was. They learn to navigate a much more mobile, dynamic world, one dominated by interconnectivity. Deckard in Electric Sheep comes to recognize the artificiality of his and everyone else’s definition of “human” by being forced to see his milieu from the outside for the first time. Rather than rehabilitating the earth or trying to protect what is left of it, the humans inElectric Sheep commodify what remains of nature in their ridiculous pet trade. If you can’t afford a real animal, you can buy a secretly fake robot critter, complete with mechanics who pretend to be vets; that way, your neighbors won’t think you’re some anti-social weirdo incapable of empathy. In emphasizing that reductionist, pragmatic definition of what it is to be human (“can produce healthy babies and will take care of them”), they’ve actually turned themselves into just another kind of machine. Blade Runner, like its source material, explores how the social construction of “productive member of society” vs “dangerous ‘Other’ that must be destroyed” comes about, gets reinforced, and eventually becomes accepted as solidly real.

And that’s pretty punk.

This essay was originally published in Bitter Empire.